The Central Role of Risk Assessment

Risk assessment stands as the cornerstone of any effective safety management system (SMS). It’s where everything starts and feeds into—or flows from. Think of it as a spider web with risk management at the centre; every element, from setting objectives and planning, incident management, and worker participation to safety in design and emergency management, connects directly back to it. Additional aspects, such as training, contractor management, and even auditing, also trace back to this core concept of managing risks.

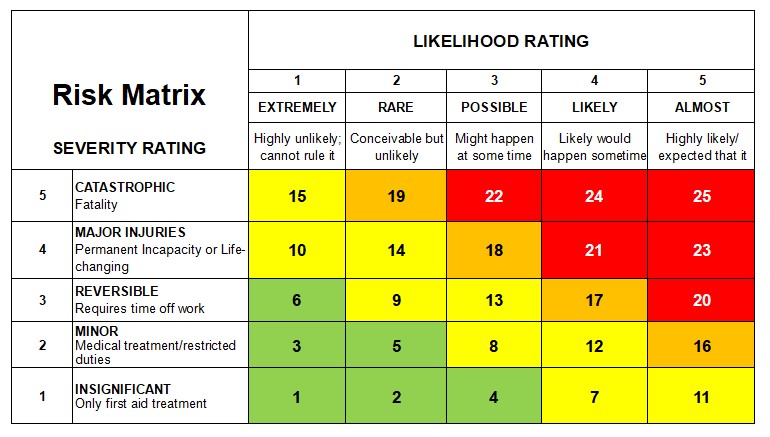

At the heart of this risk management process is the risk matrix, a familiar tool for many safety practitioners. This matrix typically features two axes—one for the potential severity of harm and another for the likelihood of such harm occurring. This exercise culminates in the creation of a “risk register,” an essential and ubiquitous component within any SMS.

Challenges in Interpreting the Risk Matrix

However, the real challenge often lies not in compiling the matrix but in understanding its purpose and interpretation. If you ask any safety practitioner about the objective of the risk matrix, they’ll likely mention “raw” or “untreated” risk alongside “residual” risk. Some may also emphasize its role in documenting control measures for specific risks.

Yet, this is where things can get murky, akin to my fox terrier chasing the school bus every day, only to seem bewildered when he finally catches it! Similarly, some practitioners struggle to explain the importance of these risk ratings. How do these numbers genuinely contribute to ensuring that employees return home safe every day?

The answer may seem simple: the risk register indicates how ‘serious’ the risk is and what actions are required to mitigate it. But moving from ‘raw risk’ to ‘residual risk’ is, unfortunately, more complicated.

Subjective Perceptions and Vague Terminology

Take the perceived seriousness of risk. To begin with, not everyone sees risk the same way. Consider an everyday scenario: some individuals won’t cross the street unless the pedestrian signal is green, regardless of traffic conditions, while others might spontaneously dart across, dodging cars. How can such diverse risk perceptions produce a uniform likelihood rating of, say, falling off a ladder?

Moreover, the matrix often uses vague terms for risk likelihood, such as “expected to occur frequently” or “could occur but is considered rare.” This only adds to uncertainty and inconsistency in risk evaluations.

Overestimating the Effectiveness of Controls

Another common issue is the overestimation of a control’s effectiveness in reducing risk. This is particularly true for administrative controls. I frequently hear people claim that administrative controls can lessen the severity of harm posed by a hazard. This reasoning is flawed; for example, no procedural change can reduce the potential severity of an electric shock, though it might reduce the likelihood of such a shock occurring.

This may seem like nit picking, but it underscores a pervasive issue: organisations often implement superficial controls and then report substantial reductions in their ‘residual risk ratings.’

A Practical Guide to Effective Risk Management

In my book, Safety 2.1: The Safety Envelope, I address these issues in depth. I offer much-needed guidance on assessing risks beyond the nonsensical “could occur but hasn’t yet” rating scales. It’s hard to expect safety science to be taken seriously with such absurd measurement tools.

More importantly, we must consider how much we need to reduce a given risk, how effective each control is, and when we’ve done enough. This is where the concept of “reasonably practicable” becomes essential, as most jurisdictions’ legislation and regulations acknowledge. There is a point at which adding more low-level controls, particularly administrative ones, is simply not necessary. It may in fact be detrimental to risk management. My book discusses how to recognise when this point is reached.

Not Cheap Talk

This isn’t about generic, off-the-shelf advice. For example, I outline a straightforward yet significantly more effective approach to assessing the probability of harm. By posing eight targeted questions, this method elevates decision-making quality without adding unnecessary complexity.

Similarly, my guidelines on determining when enough risk mitigation has been achieved strike a balance between compliance and practicality. These aren’t about ticking boxes but about streamlining safety practices to what’s truly necessary. Often, our failure to address the fundamentals results in a flood of safety instructions and procedures that overwhelm frontline workers—far beyond what’s reasonable or actionable. It’s no surprise, then, that these instructions are often ignored at the first opportunity. These are just two examples. The book is packed with practical, meaningful solutions to questions we sometimes don’t even realise we need answered.

To find out more about Safety 2.1: The Safety Envelope, click on the link.

I am really inspired together with your writing skills as well as with the layout for your weblog. Is that this a paid subject or did you modify it yourself? Either way keep up the excellent high quality writing, it is rare to look a great weblog like this one nowadays. !

Thank you very much. It’s my own work. As is my book https://adapto.co.nz/

🙂